The Invisible Trade-Off

How Cybersecurity Drains EV Batteries and the Path to Efficient Defense

Add bookmark

The automotive industry is navigating two simultaneous, transformative shifts: the transition to electrification, where battery energy density is the primary design constraint, and the evolution of the vehicle into a Software-Defined Vehicle (SDV), characterized by centralized computing, persistent connectivity, and increasing levels of autonomy.

These trajectories are creating a fundamental conflict. Connectivity expands the vehicle's attack surface, necessitating robust, "always-on" cybersecurity measures. However, security is not energetically neutral. The continuous execution of cryptographic primitives and intrusion detection logic consumes computational resources, which in an EV translates directly to range reduction.

In 2024, 60% of cybersecurity incidents within the automotive and smart mobility sectors impacted thousands to millions of assets, including vehicles, EV charging stations, and smart mobility applications. Alarmingly, incidents affecting millions of vehicles more than tripled, soaring from 5% in 2023 to 19% in 2024. In 2024, 409 new cybersecurity incidents were recorded, up from 295 in 2023, bringing the total documented cases since 2010 to 1,877. The central challenge for the next generation of vehicle architectures is therefore an optimization problem: how to maintain a rigorous security posture without critically compromising energy efficiency or thermal management.

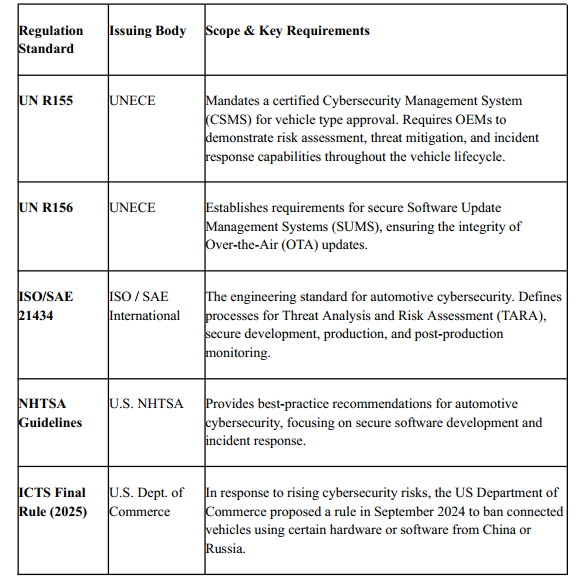

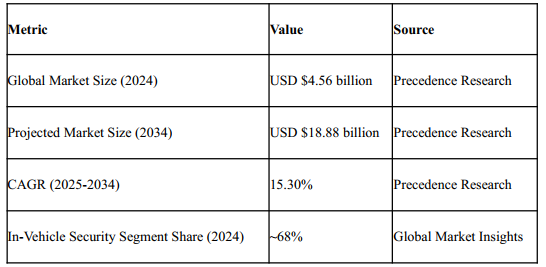

The Regulatory and Market Landscape

The automotive cybersecurity ecosystem is governed by an evolving set of international regulations and a rapidly growing market, as outlined below.

Table 1: Automotive Cybersecurity Regulatory Framework

Table 2: Market Size and Growth Projections

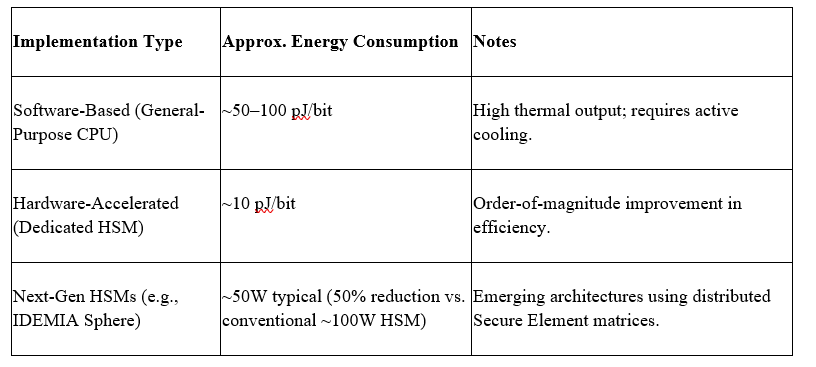

The Computational Energy Tax: A Systems Analysis

To quantify the challenge, one must examine the vehicle's communication backbone. Modern Zonal Architectures rely on high-bandwidth Ethernet and CAN-FD networks to interconnect domain controllers. To ensure message authenticity and prevent spoofing, protocols such as AUTOSAR Secure Onboard Communication (SecOC) append a cryptographic Message Authentication Code (MAC) to critical frames.

The main challenges for all these applications are to maintain confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity of the data, which can be maintained using cryptographic algorithms and key management realized in Hardware Security Module (HSM). The HSM is a specialized Hardware component designed and integrated as a part of advanced microcontroller unit (MCU) architecture, dedicated to implement cryptographic security tasks.

The energy penalty stems from the frequency of verification. While a single cryptographic operation is energetically trivial, performing it thousands of times per second creates a measurable load.

Table 3: Energy Efficiency of Cryptographic Implementations

Automotive hardware security modules (HSMs) are embedded cryptographic coprocessors integrated into electronic control units (ECUs) to protect in-vehicle systems and communication buses against manipulation and misuse. They act as a hardware root of trust by securely generating and storing cryptographic keys and offloading security-critical operations such as secure boot, encryption, decryption, authentication, and attestation.

The Low-Power Attack Surface: Denial-of-Sleep

The conflict between energy efficiency and security is most acute when the vehicle is parked. A modern CAV is never truly offline; it remains in a low-power "sentry" mode to await digital keys, remote commands, or OTA updates. When cars are switched 'off' they aren't really off: the ECUs will go into low-power sleep mode, with a tiny power consumption. They are 'woken' by a frame on the CAN bus(which typically comes from a door ECU or a wireless key ECU). This creates a potent vulnerability to Denial-of-Sleep (DoSL) attacks.

An attacker can flood the vehicle's network interface with spoofed or malformed packets. While the security layer will ultimately reject these packets, the process of inspection forces high-power processors to wake from deep sleep.

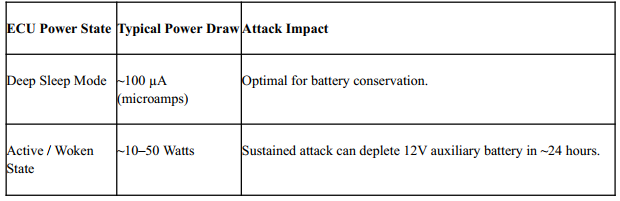

Table 4: ECU Power States and DoSL Impact

Radio interference could cause an edge on the CAN bus and cars would wake up for no reason. It became a problem for car owners who parked at the airport (where the powerful radar sweep would put an edge on the CAN bus) because when they came back from holiday, they would discover the car battery was drained.

Architectural Solution: Wake-Up Radios (WUR)

The robust defense against DoSL is physical-layer isolation. Wake-Up Radios are specialized,ultra-low-power analog/mixed-signal circuits (consuming microwatts) that listen for a specific, cryptographically signed "wake-up pattern." The main ECU power rails remain physically gated off until the WUR validates the signal, effectively eliminating the energy penalty from unauthorized traffic.

Adaptive Defense: The State-Aware Security Model

To optimize the energy-security trade-off, architectures must evolve from static policies to a State-Aware Security Model. This approach treats energy as a dynamic constraint, modulating security depth based on the vehicle's operational context and threat intelligence.

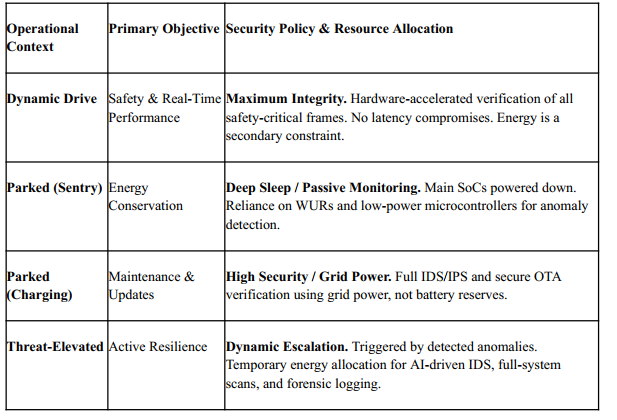

Table 5: State-Aware Security Policy Framework

Implementation Guardrails: An adaptive system introduces the risk of "context spoofing." Two architectural pillars are required: (1) Trusted State Management, where the state machine governing transitions resides in a Trusted Execution Environment (TEE); and (2) The Safety Floor, ensuring that the authentication of safety-critical actuators never drops below the threshold defined by ISO 26262 ASIL ratings.

Future Vectors: Post-Quantum Cryptography and AI

The Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) Data Overhead:

In 2024, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released final versions of its first three Post-Quantum Cryptography Standards. FIPS 203, FIPS 204, and FIPS 205, which specify algorithms derived from CRYSTALS-Dilithium, CRYSTALS-KYBER, and SPHINCS+, were published August 13, 2024.

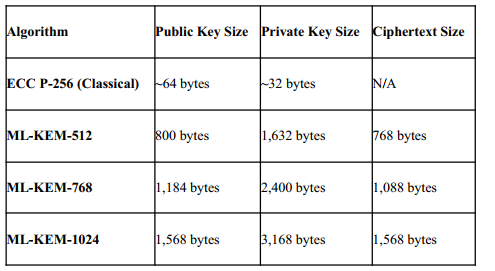

The shift to PQC introduces a new bottleneck: data volume. Especially the sizes of the private keys of the post-quantum algorithms are larger on the same security level as traditional public key algorithms. This shifts the energy cost from computation to transmission.

Table 6: PQC Key Size Comparison (NIST FIPS 203 - ML-KEM)

For vehicles, transmitting kilobyte-sized PQC certificates and signatures over CAN-FD, Ethernet, or V2X links increases channel utilization and the energy cost of the physical layer transceivers. System designers must now account for the "data energy" of security.

The Adversarial AI Landscape:

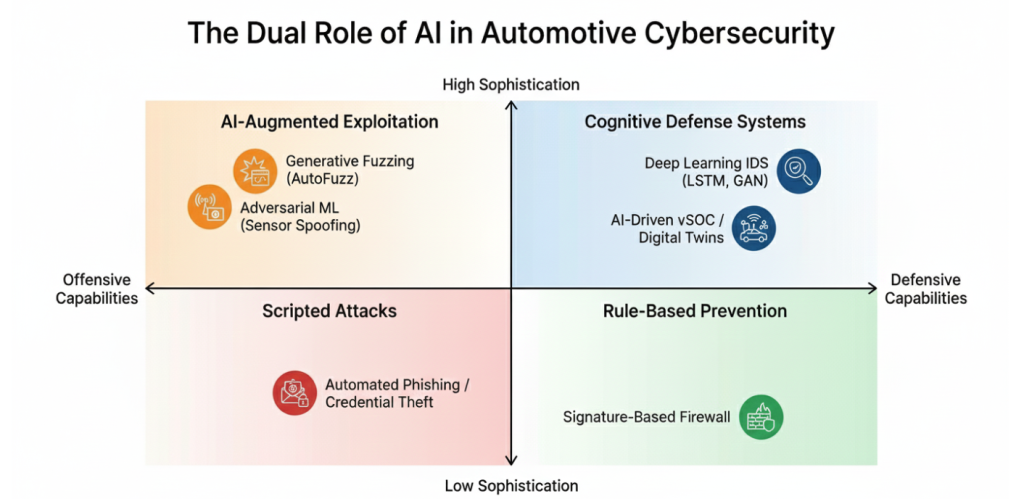

Threat actors are rapidly adopting AI technologies to amplify the scale and impact of their activities, forcing stakeholders to keep pace by enhancing their defenses. AI is becoming a pivotal, dual-purpose tool in automotive cybersecurity.

Figure 1: The Dual Role of AI in Automotive Cybersecurity

Defensively (Quadrant 1): The industry is moving from static signatures to Deep Learning Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS). Unlike rule-based firewalls, these neural networks (CNNs,LSTMs) can identify novel "zero-day" attacks on the CAN bus by recognizing subtle deviations in signal timing and voltage [9].

Offensively (Quadrant 2): Attackers are deploying Adversarial Machine Learning to craft inputs that deceive vehicle sensors and Generative Fuzzing to automatically discover vulnerabilities in safety-critical software, outpacing human manual testing [10].

Conclusion

Automotive cybersecurity has irrevocably evolved from a software challenge into a multidisciplinary systems optimization problem, intersecting battery electrochemistry, semiconductor design, network theory, and cryptography.

The data underscores the urgency: with the autonomous vehicle market projected to approach $1 trillion by 2033 and 95% of new vehicles expected to be connected by 2030, the attack surface is vast [11]. High-impact attacks enabling remote control already represent a significant portion of incidents.

Therefore, the defining question for OEMs and suppliers is now: "Is this system securely efficient?" The path forward requires deep integration of dedicated hardware security (HSMs), ultra-low-power architectural components (WURs), and intelligent, context-aware software policies. Successfully navigating this trade-off will determine the security, practicality, and consumer acceptance of the autonomous future.

References

[1] UNECE, "Regulation No. 155 (UN R155): Uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regard to cybersecurity and cybersecurity management system," United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2021.

[2] ISO/SAE, "ISO/SAE 21434: Road vehicles — Cybersecurity engineering," International Organization for Standardization and SAE International, 2021.

[3] G. Bella, P. Biondi, G. Costantino, and I. Matteucci, "Designing and implementing an AUTOSAR-based Basic Software Module for enhanced security," Computer Networks, vol. 202, 2022.

[4] A. Nsour and S. Ganesan, "Enhanced modified SecOC protocol for secure automotive networks: a comprehensive cryptographic framework," Discover Computing, vol. 28, no. 1, 2025.

[5] U.S. Department of Commerce, "ICTS Connected Vehicles Final Rule," Federal Register, vol. 90, no. 15, pp. 4762-4787, Jan. 2025.

[6] Upstream Security, "2025 Global Automotive & Smart Mobility Cybersecurity Report," 7th ed., Feb. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://upstream.auto/reports/

[7] VicOne (Trend Micro), "Shifting Gears: 2025 Automotive Cybersecurity Report," 2025. [Online]. Available: https://vicone.com/reports/

[8] D. R. Raymond, R. C. Marchany, and M. I. Brownfield, "Effects of Denial-of-Sleep Attacks on Wireless Sensor Network MAC Protocols," IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 580-595, May 2008.

[9] K. Tindell, "CAN Injection: keyless car theft," Canis Automotive Labs, Apr. 2023. [Online]. Available: https://kentindell.github.io/2023/04/03/can-injection/

[10] National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), "FIPS 203: Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard," Aug. 2024.

[11] National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), "Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization," CSRC, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography

[12] SAE International, "Automotive Security Solution Using Hardware Security Module (HSM)," SAE Technical Paper 2024-28-0037, Oct. 2024.

[13] S. Gupta, C. Maple, and R. Passerone, "An investigation of cyber-attacks and security mechanisms for connected and autonomous vehicles," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 10289-10307, 2023.

[14] Precedence Research, "Automotive Cybersecurity Market Size, Share, Growth," Report, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/automotive-cybersecurity-market

[15] Global Market Insights, "Automotive Cybersecurity Market Size, Growth Forecasts 2034," 2024.